In Flux: The Kinetic Art of Harak Rubio

THE PAINTINGS:

It is tempting to situate Harak Rubio’s work within the tradition of post-Cubist Modernism.

His work echoes voices of that illustrious past. Comparisons spring to mind: Barnett Newman, Ad Reinhardt, Helen Frankenthaler, Cli ord Still. His work provokes that impulse, to see his style as a throwback to a pre-Pop era, to the heady transcendental work of Abstract Expressionism, before postmodern nihilism emptied art of its ontological relevance.

This compulsion to view Rubio’s style through a Modernist lens, to see it as a continuation of the Modernist tradition, to recognize, in his images, the meditative stasis of Mark Rothko, con ated with the frenetic action of Jackson Pollock, is to locate his work in a more nostalgic time, when

a focus on the strict formal qualities of art retained elements of lived experience, exposing the reality of the everyday world.

This instinct to situate Rubio’s work in the humanistic tradition of Abstract Expressionism is not necessarily a negative impulse.

The problem with this exercise, trying to categorize a painter’s work—any artist, especially one as eclectic as Rubio—is that it creates a false sense of inclusion: the taxonomic tools of criticism are useful, perhaps, in a classroom, or to help a viewer with a lazy eye to understand a style by its alignment with expectations, its adherence to some object criteria of association. But these sophomoric tendencies, however convenient, deny the art its peculiarity, and in this case tend to erase Rubio’s individual encounter with life and the canvas.

After all, within the formula that de nes the Abstract Expressionist movement, Rubio mines the same vein of humanism that informs the expressive element, while stressing the non-objective formal qualities that constitute the abstract components.

This dynamic, investigating the tension between life and art that exists in the freeze frame of the painting, is the primary operating principle de ning Rubio’s work. For him, that’s where the secret, powerful con uence of life and art occurs: between intuition and conceptualization, experience and understanding, the visual and the abstract, the concrete and the conceptual, image and

the world.

The poetry in Rubio’s images relies on a central, core motif: to explore the bifurcated condition of experience, the resistance of the natural world to be contained by the plastic, the lived experience at odds with recollection, focused at a point where the natural world and the conceptual world collide. This overarching theme, for Rubio, delineates the irreconcilable di erence between the actual and the perceived, the material and the spiritual.

Nonrepresentational art creates its own language, a semiology based on limiting space, harmonizing color, balancing geometric shapes with violations of logical assumptions. The ideal of non-objective art is universality—to create images that transcend speci c cultural contexts.

For Rubio, this visual language consists of swirling images of energy, texturing layers of paint, vortices of vitality complemented—framed—by reverential spaces of contemplation. What at rst seems de nite suddenly empties itself in the vertiginous, joyful expressiveness of shapes. The canvas becomes a window opening onto life, an escape from and a commitment to form as a unifying principle of human experience.

Rubio’s lightness—the unexpected gesture, the improvisation, the formal qualities of composition whirling into images straining to contain the moment—captures the chaotic exuberance of being.

And it is this exuberant, vivacious, messy poetic muddled frenetic vision of life that Rubio feels compelled— as if morally obligated—to lock down with deliberative, logical, geometric shapes—a line, a precise rectangular square black blotch, two parallel boxes resembling mathematical equations: the tools/signi ers of logic taming emotional anarchy.

In his more recent work, the geometric intrusions highlight contrasting values among layers of texture, color and swatches of designs. But for Rubio, the violations—the lines, the blocks, the square intrusions, interposed over uid images—the contrived stripe, the geometric gesture—are never simply audacious interruptions, acts of impertinence, mere disruptions, the whim of an artist unsettling the expectations of a viewer. The geometric gures convey the calming e ects of reason trying to control emotion.

Rubio’s canvasses re ect an aesthetic attempt to harmonize two fundamental impulses of the human situation: humanism and hermeneutics. His visceral response to life, tempered by the formal tendencies of abstraction, allows him to explore that mysterious realm between the viewer and object, to reconcile what is with what seems to be, the object of thought with thought itself, where art moves from contemplation to action, giving the lie to the belief that art can express nothing but itself.

THE SCULPTURES:

Consider space a uid unity that objects disrupt. In this sense, objects do not occupy “empty” territory; they are, instead, displacing space the way an object displaces liquid when placed in water. The viscosity of space, then, becomes as material as the composition of the object situated within it. This quality of displacement gives objects their totemic power, votive energy.

Space embraces the material thingness of an object, giving the sculpted material shape. This notion of space not being emptiness but a concrete absence helps explain Rubio’s preoccupation with form, motion, and the essential natural rhythms of life he invests in his sculptures.

Not only do Rubio’s sculpted objects displace space, but, in doing so, they give form to an open area of formlessness. By disrupting the continuity of space, objects simultaneously organize it. This organizing principle of objects—capable of a ecting space—is at the core of Rubio’s fascination with the vital energy inherent in his constructions.

However, not all forms or shapes or objects hold the same potential for cosmic meaning. Closed forms, for instance, seal o space, contain it, capturing a slice, perhaps providing a de ning limit to vastness, the way a pond de nes the area of a body of water and distinguishes itself from a lake or a sea.

Of all possible forms, the circle has historically been associated with the nature of things, both cosmic and intuitive, the mystical and the intellectual. The eternal motion implied by a circle,

the perpetual reconstitution of itself, has given the shape divine qualities of perfection from Pythagoras and Plato to Hegel’s a priori synthetic knowledge to Einstein’s studies of the e ects of gravity on space to contemporary studies of advanced astrophysicists.

The mystical power of a circle is easy to understand, even for skeptics of metaphysical properties. Suggesting no beginning, no ending, only a continuous cycle of constant motion, the meaning of a circle is complex, a complete unit that implies not only closure and nitude but in nite continuation and open-endedness.

For Rubio, these contradictory qualities of the circle as a form and image are ripe for aesthetic exploitation, both for its formal aspects but also for its philosophical implications. In his view, the circle mirrors the organic movement of human experience—celebrating not only the cycles of life but also the naturally occurring physical rhythms of nature.

It is not necessarily the circle itself that intrigues Rubio. In his thinking, a closed shape implies completion, a nish, so in a way, death. However, an incomplete circle—a curved circular gure

with gaps, for instance—is an ideal shape for Rubio, o ering the best expression of where life occurs: in those gaps—at the crest of the circle, at the instant of most tension, at the hot dramatic moment of the most intense engagement, when the energy is most insistent.

In the absence of completion is where Rubio seeks the truth of experience.

A breaking wave is powerful. But the moment of crisis, as it crests and falls upon itself, just before its collapse is complete—that is the most intense moment, when the energy is most concentrated. It is the absence of completion that gives the shape—and the actual wave—its most signi cant power. A marlin leaps from the sea. At the top of its arc, at the instant of its inevitable fall and return—that is the moment of intensity, suspended kinetic energy about to be unleashed.

So it is not, fundamentally, the circle itself that intrigues Rubio but the curve that only suggests completion, if imaginatively followed to its logical conclusion. In Rubio’s vision, life is the striving of the curve for unity, without achieving it, as the essence of life is in the will to strive, to seek oneness without nality.

The simple complexity of his steel ribbons form graceful baroque shapes curving space, like strands of marsh grass bending in the wind, implying, at some distant point in the future, reuni cation, reconciliation, owing with the natural rhythms of life. His metal panels defy the bulk of their weight and solidity, the incomplete circle of a sail in full bloom, a foil lifting a ship into the wind.

The wall-mounted pieces allow, perhaps, the purest experience of his sculptures. They seem suspended, emanating an energy of their own, an arrogant independence from gravity. The upright designs, on the other hand, anchored to a base, seem imprisoned—yet, ironically, being so a xed adds a new dramatic element as the pieces seem to be striving to free themselves from their imprisonment.

As these metallic semi-circles jut into space, exploiting only the potential for completion, they return us to the need for human connectivity, re ecting unmitigated desire.

Jeff Johnson is the author of The New Finnish Theatre, The New Theatre of the Baltics, William Inge and the Subversion of Gender, and Pervert in the Pulpit: Morality in the Works of David Lynch. He has received the Florida Governor’s Screenwriting Award, The Florida New Playwrights Award, a research grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities, and two Fulbright awards. He has taught in England, Denmark, Hungary and Lithuania, and is currently adjunct professor of humanities at FIT.

____________________

”A consistent collection of weightlessness is felt when approaching the pieces. For example in the carvings there is a very flexible geometry that opens the space. Thus we seem to be facing floating arabesques whose projection reveals cosmic ambitions.

Likewise, the canvases are trustees of the free brushstrokes with which apparently he seeks to unleash colorful reflections generated from the inner layers reflected on the surfaces of each composition. In both manifestations, the artist integrates a representative action of vital cycles whose adaptability reveals special purposes. Using color he imprints tonal gradients that give thermal quality to the surfaces, and patinas on metal provide similar phenomena.

...His handling of a varied palette expressed by the mediation of strokes present the opportunity to demonstrate the participation of the artist as a protagonist in his work.

... establishes speculative guidelines that can be accessed from various angles. The not so evident is transformed into the center of attraction with the possible intention of activating the viewer's faculties for critique. In his case there is a formality that serves as an agent nourishing the conceptual."

José Antonio Pérez Ruiz

Art Critic

Catalog: Harak Rubio: Desafío y Transición, Galería Biaggi & Faure, San Juan, Puerto Rico, 2005

____________________

“Harak Rubio ... opted for a piece of perpendicular geometric interference, in the shape of a proud rectangle in which he made use of the stonemason's drill to discover the frame of mind of the block.

At the very heart of the piece, the polished circle is inspired by the womb of the Caribbean, expelling four cubes to the ground giving it an effect of life and procreation.

Harak has his own line, which he has worked above all in his cuttings of steel. Guadalajara is for him a challenge in coping with the natural volume imposed from the stone, and he has done it to perfection, knowing how to master its geometry. "

Delia Blanco

PhD in Literature and Anthropology

Art critic and independent curator

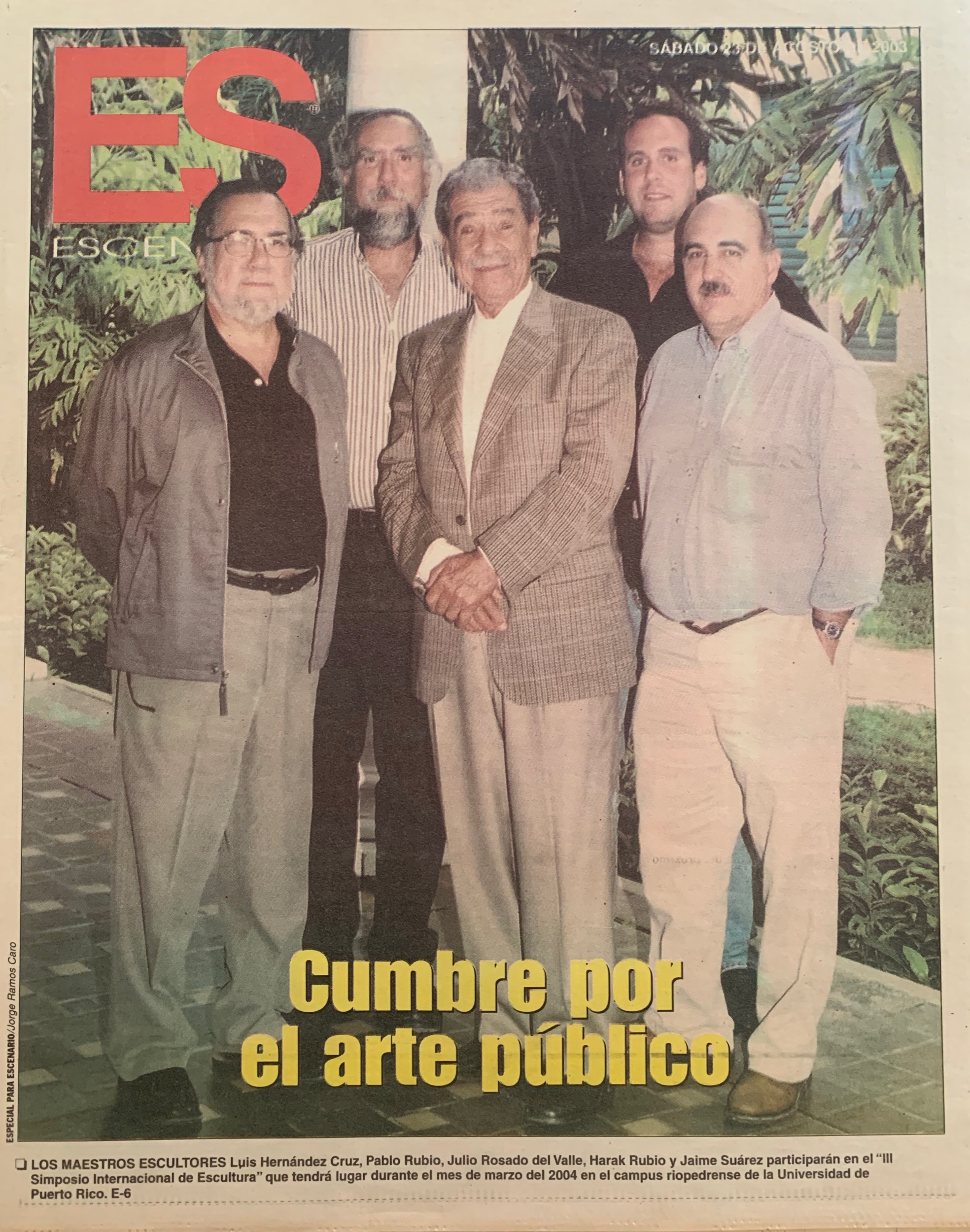

Member of the International Association of Art Critics (AICA)

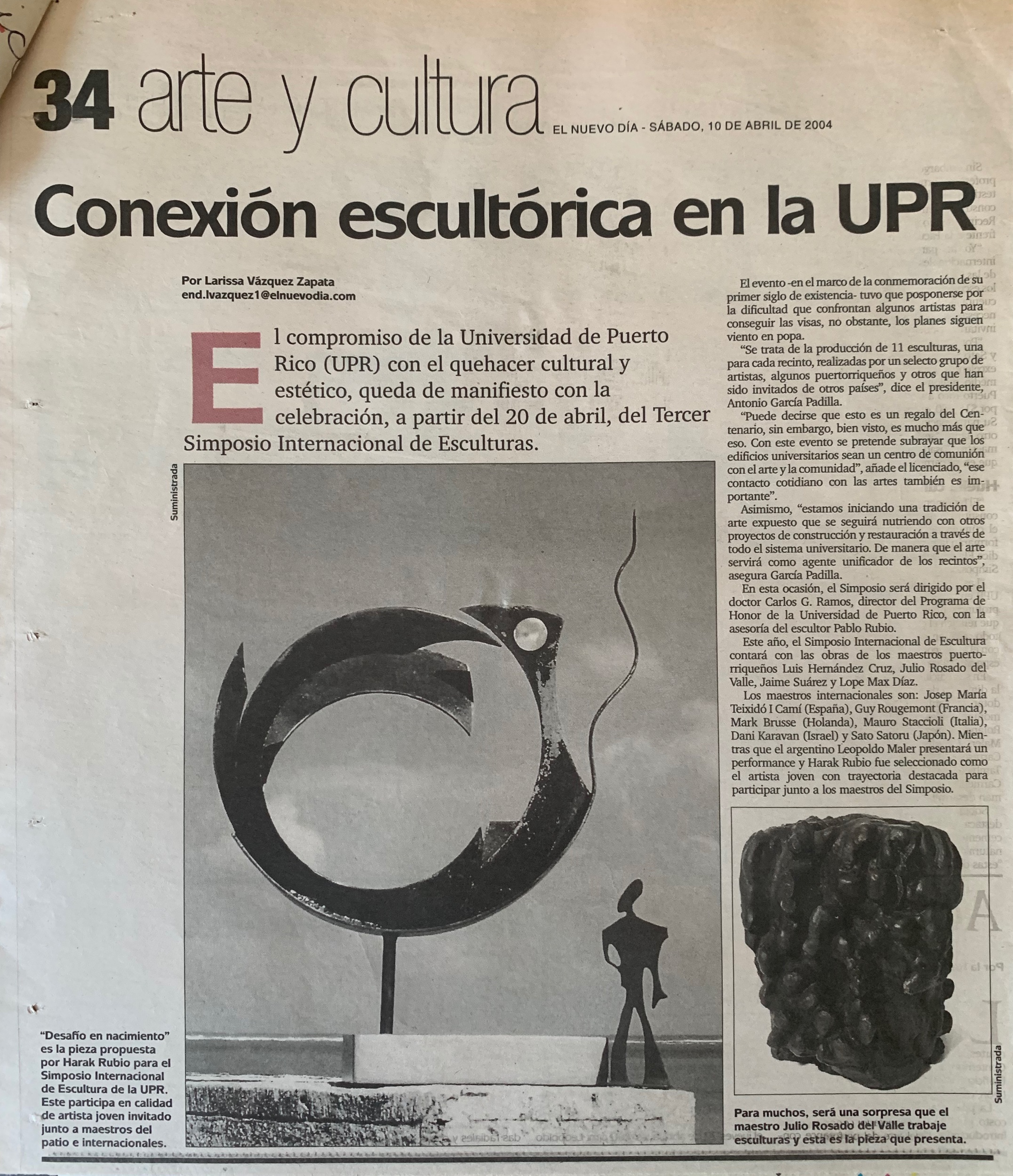

“Convergencia de la Escultura en Guadalajara”, catalog: Third International Symposium of Sculpture: Escultores del Mundo 2004, Museum of Arts, University of Guadalajara, Guadalajara, Jalisco, Mexico, pp. 2, 2004

____________________

"This same slightly baroque sensuality, connotes the split arabesques of Harak Rubio,..”

Gérard Xuriguera

International Art Critic

Asociar el arte y la vida enriqueciendo el patrimonio público”, International Sculpture Symposium catalog in the Centenary of the University of Puerto Rico, Office of the President, Rio Piedras, Puerto Rico, pp. 4, May 2004

____________________

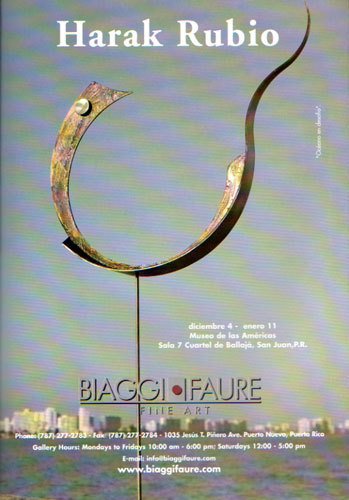

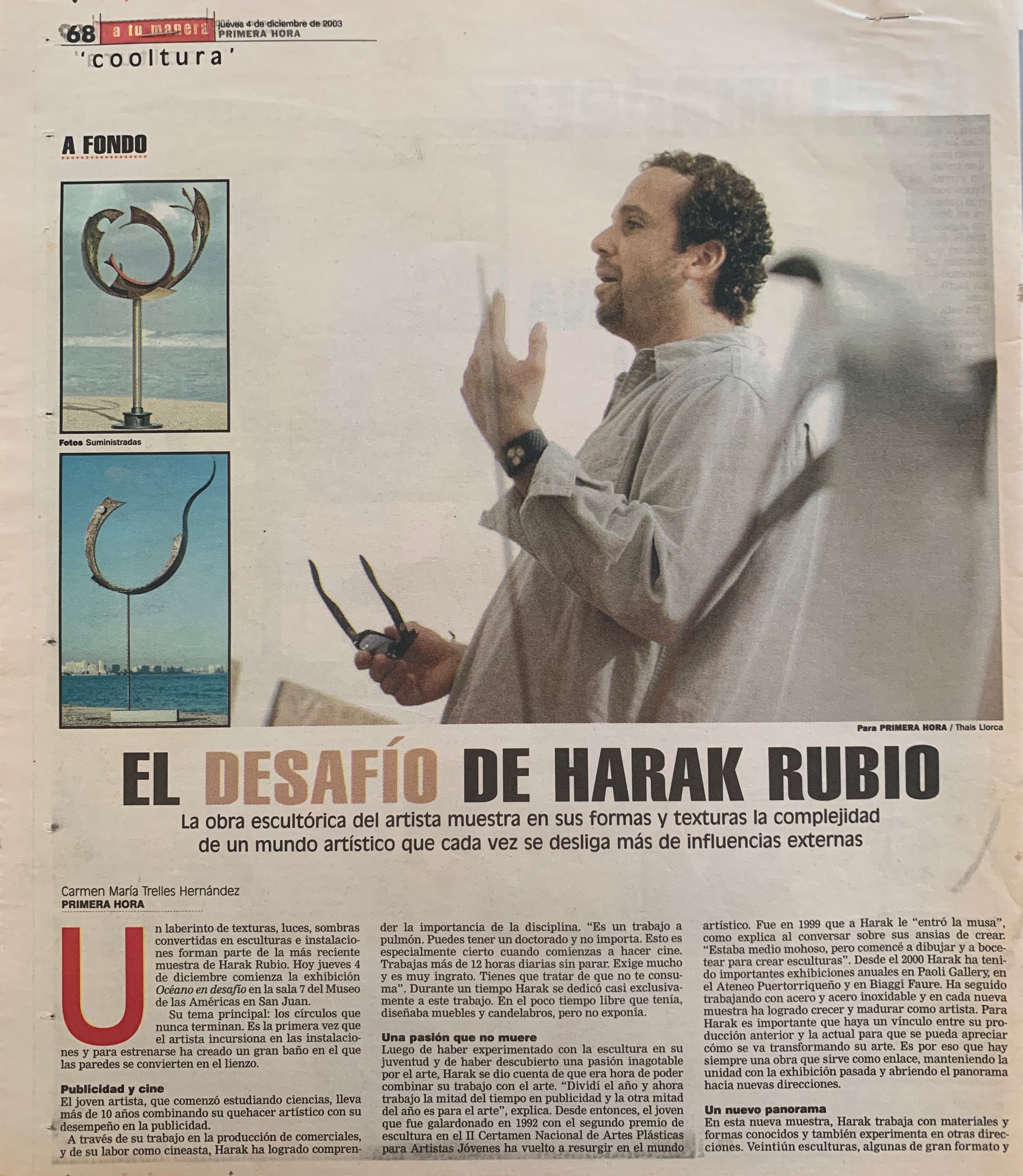

"Harak Rubio titled his present show "Oceano en desafio" (Defiant ocean), but more than water, it is the concert of the four elements, some of which, like fire, are encapsulated in the joints of the metal.

His are works in which spiritual contemplation finds its sanctuary to invoke a space of dreams from its "incomplete" circular frame...

That unfinished circle which is repeated in the symbolism of his work sometimes becomes a secret religion that retrieves icons on the horizon. Negative spaces that provide in a renewed way- technically flawless and celebratory - what has always been one of the themes in art: nature.

In its thousand alveoli, the space retains a compressed time. Therefore, here is the pentagram to read the works of this talented and multifaceted artist.

Contemplating this work by Rubio invites us to enter the same silence that allows us to recreate our "being"...

Rubio "knows" - consciously or unconsciously, that "things are not what they are but what they become." And this committed and sensitive artist turns the targets of his work into new interpretations of ancient symbols of contemplation and understanding man and his environment. "

Leopoldo Maler

Artist

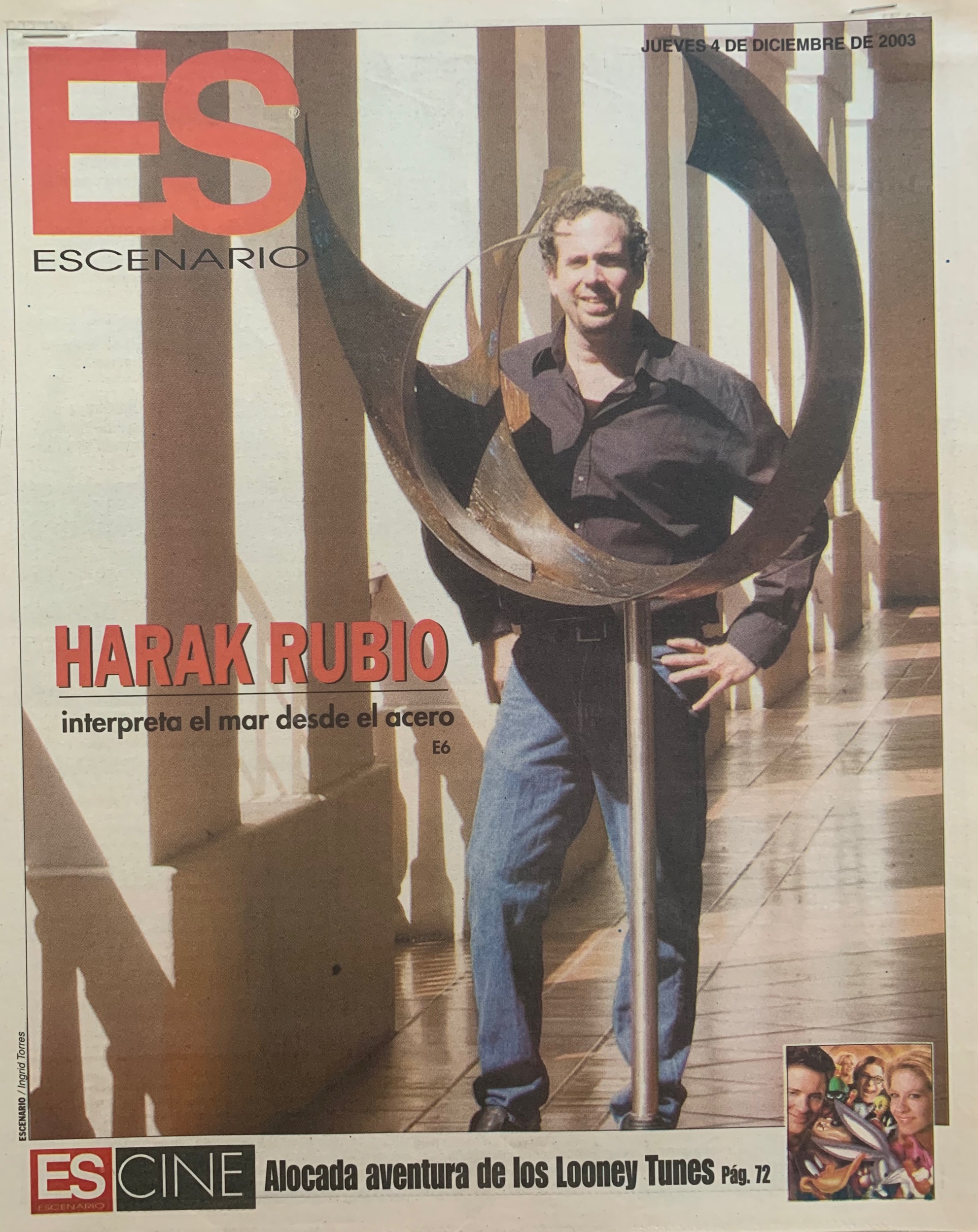

Las olas del silencio”, Catalog: Océano en Desafío, Museo de las Américas, Galería Biaggi & Faure, San Juan, Puerto Rico, December 2003

____________________

"Art surges from this particular intersection of experiences: first the interest and motivation that provide the inspiration as well as the preference for the sea that is a challenge for the scholar and navigator, second - gradual involvement with the art of sculpture with metals and third, a deep cultural background, by-product of his familial-social formation. The existential background of a vast body of experience and knowledge enables this talented young man in his creative process to achieve his artistic conception.

Marine life is the beginning, but the talented artist's originality and imagination turn nature into an aesthetic" concept."

Myrna E. Rodriguez Vega

Art critic, International Association of Art Critics (AICA)

Catalog: Mi Océano en Transición, Biaggi & Faure, San Juan, Puerto Rico, October 2002

____________________

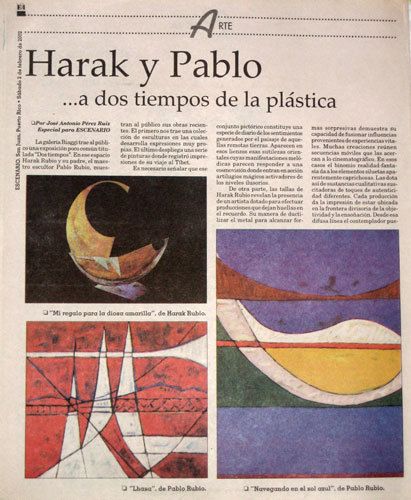

“This work was developed with future intentions speculating on the usual forms of certain species of marine fauna. Coherently, Rubio takes the current data to extract these lineal resources leading him to intuit a certain kinship with the cosmic phenomena that the new astronomical technology brings to our consideration.

The sculptor flexes the steel to snatch up a repertoire of forms that seem to wish to escape from a state of confinement in matter. The highest aspiration of this gallery of silhouettes seems to become pure movement. In this case, trends emerge in which the artist becomes liberator of the elements at intellectual levels. We note in Harak's work the prevalence of initial ideas that act as if they were hypothetical principles tested consistently with the facts. Those who observe his work will face the multiplicity of interpretative options provided by the projections of light and shadow.

An interesting matter is that Harak presents to the public a variety of shapes that possess a power of attraction worthy of mentioning. In developing the monumental potential intrinsic in each of his proposals, the island's artistic horizon will be enriched by pronouncements which strengths lie in the way he creates intense variations without leaving his thematic unity.”

José Antonio Pérez Ruiz

Art critic, International Association of Art Critics

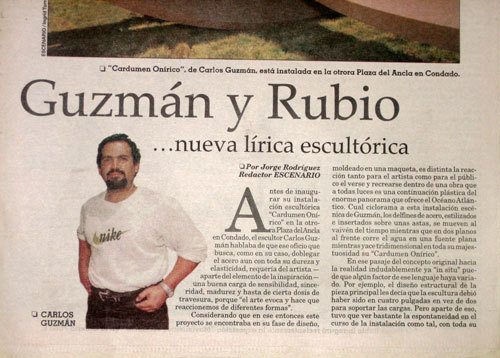

Escenario - El Vocero (newspaper), San Juan, Puerto Rico, November 16, 2002

____________________

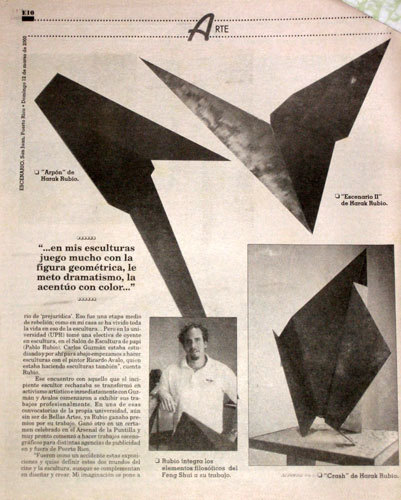

"His compositions are full of sinuous lines that take unexpected directions.

The simultaneous effect of lightness and volume that his work possesses is very attractive. On one side orthogonal lines and curves, achieve the feeling of agility, flexibility and resiliency. On the other side, the bending and folding of the metal plates create some interesting plays of light and shadows, giving volume and weight to the piece to keep it from flying before our own eyes.

... In this tribute to the forces of life, Harak builts us wings to fly to the sky on a spiritual journey then takes us closer to the land, to our origins, to be born again.”

Elaine Delgado Figueroa

Art Critic

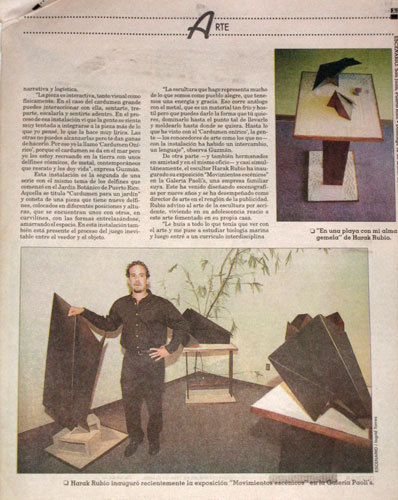

Catalog: Movimientos en Revolución, Ateneo de Puerto Rico, Paoli's Galery, San Juan, Puerto Rico, November 2001

____________________

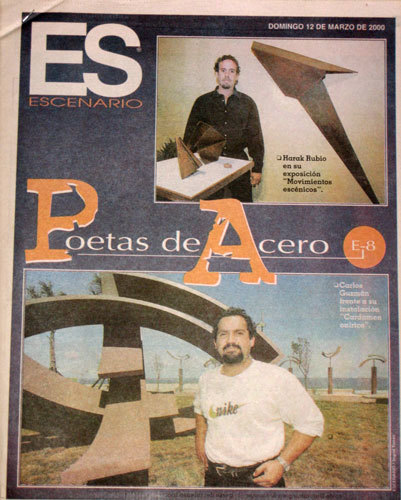

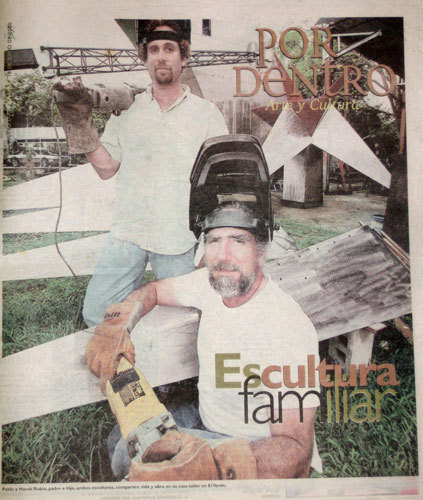

“A sculptor of steel, scene designer and father of four, Harak Rubio lives life attentive to movement, to his ephemeral universe, juggling between the making of music videos and about 140 productions of local and international cinema in Puerto Rico in recent years. Harak has evolved from the plane to the curve, to movement in revolution, to balance, to the circle in his most recent three-dimensional art ... Through the mobile sphere with patina and texture, Harak looks and focuses on a different visual universe, perhaps like the one he perceives through the lens ... the periphery is different .... This passage of rings, his approach to the metal form on a monumental scale is his proposal for the Second Biennial of the Industry of Sculpture in Steel.”

Tere Paniagua

Journalist

“Harak Rubio”, Catalog: II Bienal de Escultura en la Industria del Acero 2001, Dorado, Puerto Rico, pp. 19, 2001

____________________

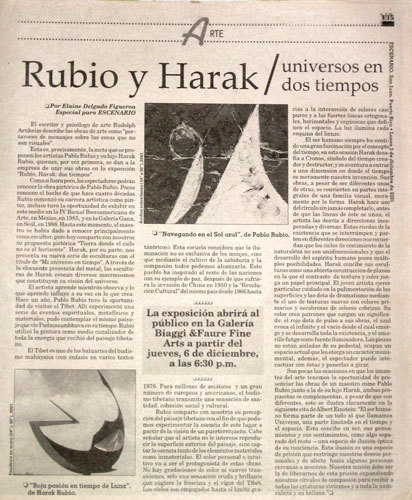

"Harak makes use of the circle without ever completing it, before its lines join, the artist detours them to diverse and unexpected directions ... conceives his sculptures as an open building of planes in which the contrast of texture and color plays a major role ... The pieces are not isolated from their pedestal, holding a current space that gives them a monumental character, in addition, the viewer can interact with them and make them turn. "

Elaine Delgado Figueroa

Art Critic

Dos universos: dos tiempos”, Catalog: rubio/harak dos tiempos, Biaggi & Faure, San Juan, Puerto Rico, November 2001

____________________

"We face an artist with sculpture and blood in his veins. A sculptor, a builder and welder, who likes the smell of solder as much as the design and conceptualization of his art.

The circle is the common thread of the works of Harak Rubio, but we never see a complete circle. It is always broken. It is as if the artist invites us to participate and to continue the conversation initiated by him. Harak celebrates in the conception of volume, open and free forms from the circular surface area where the imaginary meeting points are the attention focus. The design elements are reflected positively when light falls on the broad and gentle curves or when the contrast of textures provokes a marked visual interest.”

Adlín Ríos Rigau

President, International Association of Art Critics, Puerto Rico Chapter

Professor, Universidad Sagrado Corazón

“El Universo Presente de Harak Rubio”, Catalog: rubio/harak dos tiempos, Biaggi & Faure, San Juan, Puerto Rico, November 2001

____________________

“We are surprised and impressed with his compositions, full of life, about to take flight, about to take us to a dimension where metal and poetry are the same thing ... Part of the beauty of the work of this serious and original sculptor, is that his creations allow - and in fact invite us - to do several readings of each of them.

A big difference is that the sculptures by Harak Rubio are not mere childlish experiments, but excellent sculptures very well designed and professionally executed ... In an interview in England in the sixties, someone asked Jimmy Hendrixs what he was trying to do with his electric guitar. His answer was short but wise, "make it sound different." Harak Rubio has managed to do something different with his sculptures and I think his success is assured. His works have a metaphorical weight that makes them almost timeless."

Manual Álvarez Lezama

Art Critic

Por Dentro –El Nuevo Día (newspaper), San Juan, Puerto Rico, November 12, 2000